The Furka Pass, Rhone Glacier and Grand Hotels

1 July 2024

The film Grand Budapest Hotel (1995) by director Wes Anderson shows the decline of a hotel from the Belle Epoque, from 1900 until the First World War (1914-1918).

The Hotel Belvédère

The story of Hotel Belvédère on the Furka Pass is, as a matter of speaking, the model for this film. The hotel is, in any case, one of the most famous from this period.

Sean Connery (1930-2020 )also drove the famous hairpin bend in Goldfinger (1964) in his silver Aston Martin DB5 at an appropriate speed for 007. Countless postcards and, these days, Instagram posts show the hotel and the glacier.

The Furkap Pass, Hotel Belvédère and the famous bend. Photo: TES

Furka Pass, Hotel Belvédère. Photo: TES

Since 2015, however, the hotel has been empty. The nearby Rhone glacier is also shrinking, a development that began as early as the 19th century. Until 1870, the glacier extended into the valley to the village of Gletsch (Canton Valais). In 1980, the glacier was still opposite the Hotel Belvédère. In 2022, there is a lake instead, and the glacier is hundreds of metres away.

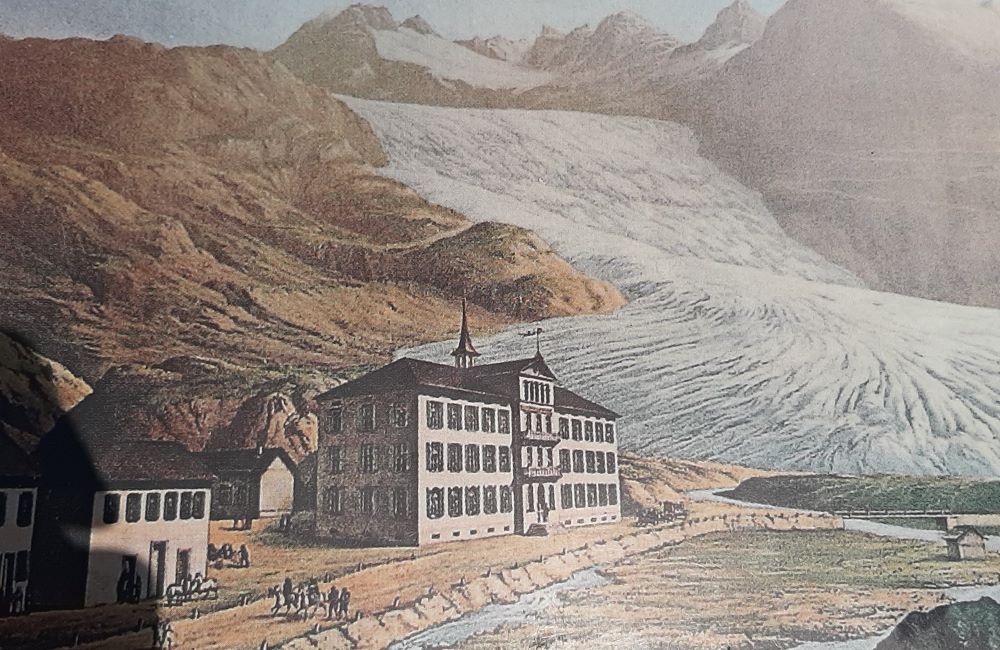

Gletsch, Grand Hotel Glacier du Rhône, around 1870. Source: Gletscherlehrpfad Furka Pass. Photo: TES.

The history of the Belvédère began almost two hundred years earlier. The first inn in the region was built in Gletsch in 1830. Alexander Seiler (1819-1891) expanded it into the Grand Hotel Glacier du Rhône in 1857.

The glacier still reached the valley and the village. The hotel was intended for travellers who used the Furka Pass or the Grimsel Pass to exchange horses and increasingly for (English) mountaineers and their large (aristocratic) entourage. The Queen (Queen Victoria 1819-1901) drank her tea here on 23 August 1868, “a delicious cup of tea”.

The Furka Hotel and the Queen

In 1850, a simple hotel was built on the Furka Pass Hotel Furka. The owner was Franz Karl Müller. The most famous guest was Queen Victoria. During her four-day stay at the hotel in August 1868, she admired the glacier and the view of the Alps but was less enthusiastic about the hotel. However, her visit ensured that the Furka Pass and Gletsch were on the front pages and in the news for many days.

The Ice Cave

It also aroused the interest of other entrepreneurs. In 1870, the organ builder Philipp Carlen from Goms (Upper Valais) had a plan: he dug a hundred-metre tunnel into the glacier, the Eisgrotte. For a fee, visitors can see the inside of the glacier. It is a great success. People queue up.

The ‘Eisgrotte‘ still exists. The entrance, however, is almost a kilometre further away. Philipp Carlen’s great-great-grandson and namesake runs the “Eisgrotte‘” today.

Hotel Furkablick and Hotel Belvédère

Hotel Furkablick. Photo:TES

The number of grand hotels increased rapidly in Switzerland between 1880 and 1914. Between 1888 and 1914, the number of (Grand) Hotels doubled from 1700 to over 3500. Alexander Seiler builds his second hotel, the Belvédère, on the Furka Pass. Franz Karl Müller also establishes his second hotel, the Furkablick.

Grand hotels are always places of progress: electricity, hot water, private sanitary facilities, and facilities for winter and summer sports such as skiing, figure skating, horse racing, golf, tennis and, since the 1920s, bridge. The hotels on the Furka Pass are modest but equipped with the most modern inventions and achievements.

The Gotthard-Matterhorn line. Photo: TES.

The hoteliers also take initiatives to build the Brig-Furka-Disentis railway, today’s Gotthard-Matterhorn line, and to widen and improve the roads over the Furka Pass and the Grimsel Pass. The three hotels on the Furka Pass (Furkahotel, Furkablick and Belvédère) and the Glacier du Rhône in Gletsch flourish.

The Great Grand Hotel Depression

But then, on 1 August 1914, the First World War (1914-1918) began, followed two decades later by the Second World War (1939-1945). The great grand hotel depression begins. On the one hand, the splendour of the Belle Époque now seems old-fashioned and outdated. Moreover, medicine offers alternative treatments so that spa cures and mountain air attract fewer and fewer visitors.

After 1960, other holiday destinations and the number of holidaymakers increase rapidly. However, the new target groups have limited budgets and holiday days. Until 1914, wealthy guests usually stayed in hotels for months.

Many hotels were demolished, burned down (whether because of insurance money or for other reasons remains to be seen) or stood empty. Only the old names in mondaine villages and towns remained open. The “Eisgrotte”, however, continues to attract many visitors.

Even Hotel Furka, the hotel of the visit of the Queen, is blown up to make room for a car park. The construction of the Furka base tunnel (1982) also meant the end of the Furka Pass as a vital traffic connection.

Hotel Belvédère in 2022. Photo: TES

The Belvédère Hotel and the Ice Cave

In 1985, Valais’s Canton took over the remaining hotels (Furkablick and Belvédère). The glacier has shrunk by hundreds of metres, and the canton wants to build a hydroelectric power station in the new lake and demolish the hotels. However, due to the population’s resistance, it does not happen.

Right on top the Furka pass, Hotel Belvédère and the disappeared glacier. Photo: TES

In 1988, the canton sold the Hotel Belvédère to Philipp Carlen, the current operator of the “Eisgrotte”. The hotel reopened in 1990. In 2015, however, it closed its doors (for good?).

But Philipp Carlen also has other initiatives, a glacier nature trail, an alpine garden and soon a slide for children. He also wants to rent out boats on the lake.

Only the Hotel Furkablick still has a function, namely as a gallery. There is new hope for the Hotel Glacier du Rhône in Gletsch. There are plans to reopen this grand hotel in 2025 after renovation. It is part of the revival and upgrading of Grand Hotels that have been taking place since the end of the 20th century.

The Revival of Grand Hotels

Swiss Historic Hotels, founded in 1995, plays a role in this revival. Other Grand Hotels such as the Badrutt’s Palace, the Kulm Hotel and the Suvretta House in St. Moritz, Les Trois Rois in Basel, the Kurhaus in Bergün, the Bellevue in Scuol, the Montreux Palace, but also hotels in smaller towns such as Maloja and Celerina are just a few examples of an almost unbroken continuity from the Belle Époque era, even if only a few hotels have remained independent.

Other Grand Hotels, such as the Val Sinestra in the Lower Engadine, have used the splendour of the past for other purposes. However, many Grand Hotels are waiting for investors and renovation.

Grand Hotel Celerina, Upper Engadine. Photo: TES

Grand Hotel Maloja, Upper Engadine. Photo: TES

Suvretta House, Upper Engadine. Photo: TES

Hotel Les Trois Rois, Basel. Photo: TES

Continental Parkhotel (the former Grand Hotel Beauregard), Lugano. Photo: TES

The future of some Grand Hotels is uncertain. However, the “Eisgrotte” will be gone within two generations. That is a certainty.

The glacier in 1980, on the left of Hotel Belvédère. Source: Gletscherlehrpfad. Photo: TES

The lake in front of Hotel Belvédère in 2022. Photo: TES

The Rhone Valley, view from the Furka Pass. Photo: TES